The history of female eroticism in Arab Literature: An interview with Selma Dabbagh

"The erotic, particularly concerning women in the Arab world and for women of Arab heritage, has become a very tricky terrain to navigate, there is the spectre of Orientalist voyeurism and salacious pornographization, and the more recent Islamophobic permutations of the same idea, which transforms women from being hyper-sexual to being non-sexual."

11 Kasım 2021 10:08

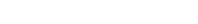

The anthology, We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers, edited by Palestinian-British writer Selma Dabbagh and published by Saqi Books, brings together a selection of the works of 75 women writers and documents the history of female eroticism in Arab Literature. Reminding us that writing about love, desire, and sex is a historical phenomenon in Arabic literature, the anthology embraces women's legacy of passion and creativity and provides a continuum from Abbasid poets to contemporary names.

![]()

The collection is called “We Wrote in Symbols,” named after a poem by the Abbasid princess Ulayya bint Al Mahdi. Symbols suggest and signify, and they often contain an intellectual strategy to reframe the reality around us, creating verbal bonds between the concrete (hissi) and the abstract (ma'nawi). So, tell me, what was your strategy curating this anthology?

This quote from Ulayya Bint al Mahdi was chosen for the title as her spirit really encapsulated what we were trying to achieve with the collection. My impression of her is that she loved passionately and sought to transgress any boundaries placed on her passion. She saw no shame in her love, both physical and emotional and communicated to her lovers, of both sexes, or none, through a variety of creative missives. She demonstrated temerity, creativity and daring, which she needed despite her position in the Court and the admiration of her powerful brother (Haroun Al Rashid). I love the distinction that you make between the concrete (hissi) and the abstract (ma’nawi), but I am not sure that the bonds made by symbols are always verbal, they could be just as abstract or ethereal, a symbol, or a new, fresh image communicates a new world, or can make your world appear new. But then again, to speak of words, John Steinbeck in interview once said that ‘the craft or art of writing is the clumsy attempt to find symbols for the wordlessness. In utter loneliness a writer tries to explain the inexplicable.’ At risk of being tautological, the writer experiences, or evokes an experience, in an abstract way, attaches symbols to it, through words that creates images and impulses, with the hopes that it will communicate a emotional bond through time and place, although their control over how this is constructed or received is rarely precise, nor should it be.

The strategy in curating the anthology was to find pieces that communicated desires of love and lust through the millennia, often written by women who fluctuated between communicating the abstract and the concrete. I wanted the collection to reflect as much diversity as possible among women of Arab heritage, in terms of religions, languages, sexualities, experiences and writing styles.

The book consists of one hundred and one piece by seventy-five different women from the Middle East and North Africa region, as well as from the diaspora, representing the strong tradition of Arabic writing on love and the erotic stretching back several millennia. I think this book functions as a portal that allows us the opportunity to transport ourselves into a boundless land of female lust and desire. The definition of Arabism that holds these works together is flexible, floating and receptive. Still, this book is the result of extensive research. It is clear that you've considered various criteria. Can you tell us how you found and combined these authors?

I am grateful to you for appreciating and grasping the concept of the anthology. The erotic, particularly concerning women in the Arab world and for women of Arab heritage, has become a very tricky terrain to navigate, there is the spectre of Orientalist voyeurism and salacious pornographization, and the more recent Islamophobic permutations of the same idea, which transforms women from being hyper-sexual to being non-sexual. The Arab world is also interesting in that it had one of the oldest, if not the oldest histories of female literacy and the role of the female poet dates back to the Jahaliyya period, but also some of the highest rates of female illiteracy. The concept of female desire has also been celebrated and shamed at different periods over time. The collection sought to provide a unique insight into how women writers themselves responded to the societies they lived in, the relationships they experienced, the fictive characters they developed, by showcasing their writings, in their own voices, rather than seeing them through an outsider gaze. I also believe that the perception of monolithic cultures is dangerous and erroneous. Culture is always heterogeneous. It is constantly being challenged and reformulated.

How I found the writers was via a mix of different sources. There are two main anthologies that I relied on for the classical works, Classical Poetry by Arab Women, edited and translated by Abdullah al-Udhari (Saqi, 1999) and the Wessam Elmeligi collection The Poems of Arab Women from the Pre-Islamic Age to Andalusia (Taylor Francis / Routledge, 2019). I also spoke to academics who provided some additional leads and included one non fictive work, a letter by Zad Mihr from the 11th Century Baghdad, which had recently been translated by Prof. Geert Jan van Gelder and Emily Selove. Some of the modern stories and novel excerpts I had decided upon before I started the project (works by Hanan al-Shaykh, Ahdaf Soueif, Hoda Barakat, Leila Slimani for example), others I found when researching around it. I was keen to encourage unpublished writers so around five pieces are from writers who had not previously published. Translators also played a vital role in identifying writers in French and Arabic whose works are not known in English or had never been translated previously (Samia Issa for example).

The anthology does not follow the chronology. The pieces are not interrupted by biographical information, either. For a broader context, it is necessary to go to the back of the book. I think it's a brilliant strategy, in line with the nature of raw desire -a desire beyond its personal and historical significance. What was your aim with this editorial choice?

It took some trial and error in determining how to order the pieces as the breadth of them was so wide and how they connected with each other was often quite unexpected. I worked very closely with a Senior Editor at Saqi, Elizabeth Briggs on final selection and ordering. Once we had collated those pieces that we wanted to include, at first started ordering them chronologically. The advantage of this is that is shows the forthright nature of the classical women (c.2000 BC – 1492 CE) poets on issues of love and sex, as well as the moratorium of around 500 years in writing on these subjects by women, between the fall of Andalusia in 1492 to the late Ottoman period. I instinctively felt, however, that the collection could read like an academic tome with the older, shorter poems at the beginning, which would deter some readers. I then played around with ordering the poems according to the emotional moment, or the personality of the narrator of them, working with Tarot like archetypes e.g. the Virgin, the High Priestess etc, but it was sometimes a bit forced. Ultimately, we decided to detach the dates from the works in order to subvert assumptions about women’s approaches to this delicate, controversial and essential parts of their existence and to focus on how the pieces essentially ‘spoke’ to each other. We called it our emotional algorithm. I did some final rejigging at the end as several of the pieces were very sexual in content and sexual content can make readers balk – it really depends on the mood of the reader at the time, they may not always be in the mood for it – to give the readers breathing space between the more explicit descriptions. Not having dates and biographies under the pieces was also important in encouraging readers to look up the biographies of the women, for the writers are as impressive in the way that they live as they are in the way that they write, and to be surprised by the time periods that some of them lived in.

In your introduction, you note that several Arabic literary periods, the Umayyad and Abbasid eras and the Arab rule of Andalusia, embraced a remarkable degree of openness around women’s desire and sexuality. You also write:

….during early periods of Islam and pre-Islam in the Arab world, sexuality did not have the heteronormative assumptions that existed elsewhere at the time. It was not until the Western imperial legacy, including the works of Sigmund Freud, crossed the Mediterranean into the Arabic language, that categorizations began ‘erasing the more extensive and flexible medieval Arabic model of sexuality, declaring it “deviant” [imposing] instead a binary view of sexuality onto the Arab world’.

Following this quote, one can start questioning the Western myth of progress. I think this anthology offers such a unique perspective on this dogmatic relationship between progress and modernity.

Thank you. That is good to hear. I like that expression ‘the myth of progress.’ It is such a dominating myth, hard to rebut when so many of us are addicted to modern day excesses. At one point I wanted to include the outburst by the Egyptian film director Youssef Chahine when he objects to his interviewer, Mark Cousins, using the term ‘third world’, in the introduction, ‘I’m a third world?’ he bursts out with, ‘No, you are. The Third World? Jesus Christ! I’ve been around 7,000 years and we’ve proven that we were civilised 7,000 years ago. We’re so underdeveloped? That’s not civilisation! Civilisation is how do you contact with other people. Do you know how to love? Do you know how to care? This is civilisation.’ I love that. Human desire, romantic and physical, are such basic drivers of human action, measuring civilization in terms of how they are realized and sustained would be a far better way of looking at the world than how many possessions we have. I cannot pretend to have expertise in this area, but my understanding from some of the scholars I spoke to that during the Abbasid period, sex, was according to one of them ‘a way of life,’ which included the sexual satisfaction of women to provide some of that balance. I am blurring out some of the inequities in Abbasid society here, e.g. concubines, slave boys etc, but the idea that harmony in a couple should influence harmony in society is a powerful one, taken on by revolutionaries and conservatives, some for the benefit of women and others to repress them.

I always find it shocking that scholars often fail to mention the influence of Andalusian homoerotic poetry on the evolution of the sonnet tradition. This is why works like yours are of great importance. To prevent the loss of historical and cultural links that have been ignored for various reasons.

It is an important and exciting time to be working on this area. There are a lot of re-evaluation, re-accreditation going on the influence of Arab / Muslim science, architecture and philosophy on European thought and also on the story telling and poetic traditions, from the 10th century poet Al Ma’ari’s influence on Dante, to the Muslim influence on Christopher Wren (see the work by Diana Drake) and Ibn Rushd’s influence. Expertise in the genesis in storytelling and poetry is a field beyond my own, but I was very fortunate to be invited to several workshops run by Marina Warner and Wen-chin Ouyang on Arabic Stories and Poetry in Translation and to be exposed to the work of the Library of Arabic Literature (NYU-Abu Dhabi) which has produced some excellent new translations of neglected Arabic texts in bi-lingual volumes. People of Arab origin, who are not fluent in the Arabic language, like myself, are now able to regain access to their heritage, through the works of these scholars, translators and publishers.

The anthology also provides an almanac of possibilities for writing in Arabic about sex, desire and the body. Anthologies are often anchored in the past, but one of their primary importance is offering new horizons for the future. So what do you think is on the event horizon of this book?

Neither a writer, nor an editor has full control as to whether their intentions are ever realized and often they are not particularly consistent as to what their intentions may be, for a book is an evolutionary project, where you develop with the work. I hope that the anthology brings the writing of more Arab women writers to the fore, enables for greater daring in terms of creating narratives which contain more of a erotic pulse to them – for if you can write the erotic well, it is my belief that you can write anything, for no subject is harder. It would be great if more research is done into women’s writing up to the present day and for the work of the translators, scholars and editors of these periods is brought to the fore more.

One of the contributors of the anthology, Leila Slimani, recently said that her editor told her that the word she uses most often in her books is “shame,” and added, “….in Arabic, we say that someone who is well educated is someone who feels shame.” This quote made me think of another piece in the anthology, written by Salwa Al Neimi, in which a scholar evokes memories from her life, among them her sexual relationships with “thinkers.” What do you think about the conceptualization of shame? Do you think this is an effective exercise considering the fact that shame is one of those words that is usually associated with the sexuality of Arab women?

This is the most complex question of all. I am not sure I can do it justice. One is inclined to generalize and to look at all women of Arab heritage over all periods covered in the anthology and draw conclusions about the concept of shame, a task which is next to impossible and distorting. As I see it, conservative concepts of ‘shame’ and the articulation of female desire run contrary to each other. One of the first reviewers of the anthology for the Times Literary Supplement Zahra Hankir started her review by saying that there was no talk of sex or the erotic growing up in Lebanon, that the subject matter was closed down on by the words of shame (aib) and prohibition (haram). However the term ‘shahwa’ (desire) has, I understand it, a neutral, almost cerebral, connotation in Arabic, although how female desire has been catered for, or clamped down on, has varied over time. There have always been restrictions though in terms of which types of relations it could be expressed within. I would be foolhardy to deny this. Restrictions range from the legal, social, familial and vary according to location, class and religion, but where there are restrictions, there is always resistance. In the 1964, the Lebanese writer, Layla Baalbaki, was taken to court for her short stories Spaceship of Tenderness to the Moon, which expressed, in fairly muted terms, female love and desire. As Roseanne Saad Khalaf points out, her use of the first person narrator by a female writer, being seen as extremely controversial in itself. We have moved on from here.

The anthology aims to push back on the accepted view that conservative constructions of shame have always prevailed unchallenged in the Arab World. Whereas most books on Arab women in English focus on how desire is repressed, this anthology strove to look at those who articulated it with craft, often using coded speech to allow for avoid the restrictions existent at the time, re-arranging power dynamics in the way that Salwa al-Neimi’s narrator does with poetry. The subject matter often called for development of poetic form, as with the work of the ‘lewd ones’ the group of poets that included Abu Nawas and Inan Jariyat an-Natafi during the 9th century CE. On the intellectualization of the erotic though, as far as I understand it from the classic work of the Tunisian sociologist, Abdelwahab Bouhdiba (Sexuality in Islam, 1985) and others, there was a strong tradition of this, particularly during the Abbasid period, where erotic studies were not seen to be of any lesser value than say astronomy or engineering. Mind and body have not necessarily been seen to be in opposition with each other in terms of the realization of intellectual achievements; that dominant way of clamping down on the sensory, stems more from the traditions of the Stoics and Romans, like Marcus Aurelius, and the colonial rulers who were inspired by these classical thinkers. At points in time in the Arab world, the articulation and realization of sensual and romantic desires, was seen as part of the greater good of society as a whole, which is reflected in the writing of some of the earlier women poets.

Lastly, how has working on this anthology influenced your writing? Have you ever felt provoked? Or do you feel challenged by the tradition?

It’s made me want to push myself more, both as a writer and as a person. To be more truthful to myself, freer in my imagination, more daring in taking risks for the issues and causes that I believe in, both privately and publicly. I feel humbled by my connections with the women writers in We Wrote In Symbols and I am proud to have worked with them.

•