“Imagine a country without fear”

How I discovered a tender new ‘theater of cruelty' in the work of Greek artist Maro Michalakakos and what it showed me about fear and freedom…

04 Ocak 2018 14:00

Discovering a good artist is always a thrill. With Greek artist Maro Michalakakos, it was also a revelation. Her works enthrall me, as if someone else has given shape to my dreams, my deepest fears, or my most cherished longings.

The feeling is very similar to finding a new writer who jolts you and reverses all your expectations. It happened to me recently when I started reading Mikhail Shishkin, for example. All my reading habits were shattered in a moment. With Maro, too, I experienced a sea-change, she revealed me to myself. My hidden longings crept up on me from all sides. The drama was striking.

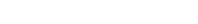

The kind of drama I encountered in Maro’s work is almost baroque in its blood-clot intensity. A brand-new theater of cruelty has come visiting, is the only way I can describe it. Later, I realized that I had wished for something like this, perhaps we all have, all of us, personally or globally, desired some uplifting, soul-shaking emotional experience to match the cruel deceptions of our present world, the traumas we suffer or witness daily, the sadness we need to process. Maro Michalakakos stages all these emotions with aplomb and great skill.

It is the theatrical aspect of her vision, the performative drive in many of her installations, that give her works so much emotional power. They resonate with deep existential anxiety, sometimes with a quirky humor, and always with exquisite beauty.

It must be partly due to the allure of the red velvet which she frequently uses in her works. She truly is a scarlet woman. The red cloth highlights the drama she seeks in the hidden folds of life –the drama of abandonment for one, not only the mundane kind that happens in love, but something deeper, at times even social, like being forsaken, almost. There are also intimations of incarceration and the kind of implicit, as well as outright violence with which male dominated society constantly keeps women at bay. She simulates that violence in unexpected ways.

This is an artist who shaves velvet with a scalpel. She makes pictures by scraping the fabric. Thus icon-like portraits appear on the cloth, of wretched, emaciated women, like shadows, with sunken eyes and skeletal hands. These are images of heartbreaking sadness and solitude.

This is an artist who shaves velvet with a scalpel. She makes pictures by scraping the fabric. Thus icon-like portraits appear on the cloth, of wretched, emaciated women, like shadows, with sunken eyes and skeletal hands. These are images of heartbreaking sadness and solitude.

You feel as if archaic imprints on a cave wall are revealed for the first time to you, the viewer. You are ravished. Or again, it could be the Madonna in a sunken church in some forgotten place, or yet again, an Etruscan face in a long-lost tomb chamber, never seen before. You just don’t know. It is like an archeology of deep human suffering and compassion, as these sorrowful shadows gaze across time, onto infinity perhaps. The time in which they are sequestered may be infinite or from yesterday. They are like lost souls in purgatory. They remind me of the faces and postures of women who have suffered in war, caught in catastrophe, or sometimes shut away in some peculiar solitary confinement or depression.

She does other clever things, mysterious things with the red velvet. You might find a long-chair, perhaps a psychoanalyst’s couch, again upholstered in red velvet, from which many large eyes stare at you, etched (or shaved in this instance) with a nagging decorative insistence.

You might encounter a gilt-framed, blank oval mirror, in opaque red velvet, with only a dark pubic triangle scratched below, triggering fearful fantasies. (I could have almost said “guilt-framed.”) In the normal everyday interiors and their trappings, curtains, or sofas and fabrics, Maro Michalakakos goes in search of the uncanny.

In another, wide red velvet panel, the white spots look like ordinary prints from afar, but drawing close, you find dozens of regimented skulls staring at you. Shavings of red cloth rise in huge mounds, with an ironic gesture towards Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days.

Two adjacent chairs are almost intertwined, and on the upholstery of the back-rests are again shaven the faces of two lovers, desperately trying to reach each other, but forever captive in their respective fabrics. The seats of two other chairs, now facing each other, are etched with more skeletal hands; the title reads “fortune- teller.” A large ordinary looking dining table with plush chairs is over-hung with a chandelier of gnarled branches that could easily double as viscera. A red velvet ribbon goes through the eye of a giant needle and loops with no open end in sight, like blood circulating. It is also a snake chasing its tail.

This is the artist wandering in a wonderland we all seem to share, and in it she can be quite playful at times.

But the interplay of body parts and furniture, the shadowy women in velvet weren’t the first works of Maro Michalakakos that I saw. My initial encounter with her art was through her fascinating birds.

Trailing a seductive cruelty

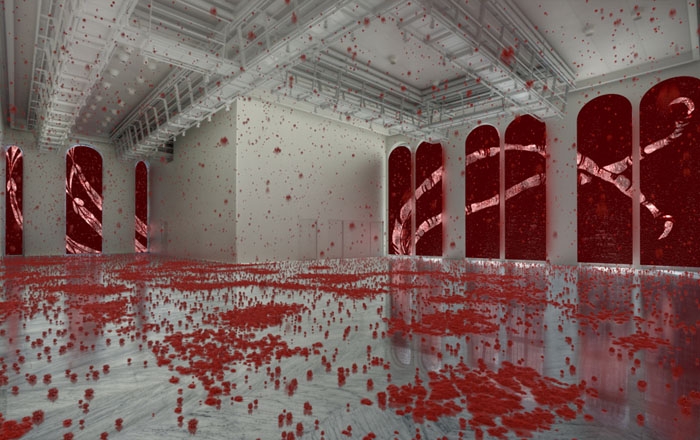

It was November 2016, I was wandering through İstanbul Contemporary Art Fair, enjoying the various art works, when I suddenly turned a corner and came to face a magnificent pink flamingo painted in luminous water-colors, tangled with a scorpion. Another flamingo was clearly in much deeper trouble, it had twisted and knotted its neck around its own leg. Perhaps it is because I was in trouble too, at the time, that the gesture appealed to me.

There were other birds, pre-occupied with other obstacles, bright in plumage but dubious in genealogy, up to no good. The draftsmanship and the colors were lovely, like 18th century scientific nature drawings, though not so innocent or placid. There was something deeply unsettling about these birds, beside their beauty. I was captivated. I needed to get more information on the artist.

There were other birds, pre-occupied with other obstacles, bright in plumage but dubious in genealogy, up to no good. The draftsmanship and the colors were lovely, like 18th century scientific nature drawings, though not so innocent or placid. There was something deeply unsettling about these birds, beside their beauty. I was captivated. I needed to get more information on the artist.

The more I found out about her, the more fascinated I became. It turned out she had already participated in an exhibition at the İstanbul Modern Museum, precisely with some of these strange birds and the co-curator Paolo Colombo had said of them that they were “an archive of mythological animals, that through interspecies mating, become the chimeras of our times.”

This made some sense, of course, but was too fancy for me. Looking at these fantastic birds, I kept asking questions to myself: Do birds get angry? Are birds also exasperated sometimes? I had a sense that the creatures wanted to communicate something to me. The artist had somehow contrived to represent the terribleness of life, as well as its heart-wrenching beauty.

In one water colour, Head Over Heels, two of these quaint birds embraced, in what seemed to be a grip of desperation, rather than joy or companionship. The beautiful feathers concealed untold violence. I suddenly understood why we humans are cruel to each other and to ourselves. I didn’t feel that the artist intended any anthropomorphic metaphor, just that she communicates emotions through very unusual means.

In one series called “Parallel Universe,” serpents coil around peacocks; a cormorant has caught in its beak a lizard, whose tail penetrates its eye; a flamingo has wrapped itself around a bear; a mouse is sucking the neck of an owl. You don’t know if these are improbable amorous couplings, humorous tales, or dark visions of violence and death. The beauty of the water colours suspends all judgement.

As my enthrallment grew, we moved into 2017, and I got lucky. She had her first solo show in İstanbul, at Gallery Nev. I found this out too late though, I just made it to the show as it ended, and finally encountered the red velvets, the drama of the faces and the eyes. Throughout that stark show, I kept thinking: Rarely does so much tenderness and wry humour come together which such a sharp sense of the cruelty in life. Rarely does such a darkly theatrical, baroque sensibility mould so easily with a deep mindfulness of the moment, such attention to the transitoriness of life.

In Maro Michalakakos’s art, all was fleeting, and all was tangible presence. I was delighted. I felt I had to meet her. This also happened to be the peak of my ten-year love affair with Athens and Greece. I was due to visit again soon, in April 2017, for the opening of Documenta. This was my chance. I got her address and wrote to her. She replied warmly, agreed to a meeting.

In Maro Michalakakos’s art, all was fleeting, and all was tangible presence. I was delighted. I felt I had to meet her. This also happened to be the peak of my ten-year love affair with Athens and Greece. I was due to visit again soon, in April 2017, for the opening of Documenta. This was my chance. I got her address and wrote to her. She replied warmly, agreed to a meeting.

And so began a friendship.

To describe her personality, I shall borrow a quote from Shishkin – “a bundle of passion, raw emotions, and rare power.” We hit it off from the first moment. I remember a long drive in her car, deep in traffic and deep in conversation.

She invited me to her studio, near the Kolonaki district of Athens, a large, ordinary flat in an apartment building, very familiar to me from the studios of many artist friends in İstanbul. I immediately felt at home. Athens and İstanbul are like bizarre mirror images of each other, exactly like Maro’s parallel universes; what’s straight in one is upside down in the other, and all seems familiar in a strange way.

Getting to know her, albeit only scratching the surface, I began to understand better the unusual drama in her work. Her father has an antique shop, in a building right across the street. I could sense the kind of colours and textures she had spent her childhood in. She remembered helping her mother on sewing days as a young girl. She grew up in Athens, but comes from the Mani; she is the daughter of a region rich in mysterious beauty, with a past of equally enigmatic violence, at least if Patrick Fermor’s travel book Mani is to be believed. She studied art in Greece, France, and Germany.

Wandering around in her spacious studio, I realized her hold on me: She has done what I still seem to be struggling with; she has freed her imagination, completely. Not an easy thing to do for a woman, especially in a country like Greece.

I realized something else. Ever since my first encounter with her work, I kept asking myself if there was any precedent, whether she reminded me of any other artists. The answer is no. What are her references in modern art? I could find none. She is totally unique, astonishingly original, exactly in the way Louise Bourgeois was original. She has brought forth all this uncanny, captivating imagery from her own inner world.

She told me that the red velvet represented boundaries for her, the limits that she wanted to overcome; in Orthodox churches, the red velvet curtain conceals the inner sanctum, where women are not allowed. Shaving the velvet, like hair, gives her the satisfaction of symbolically cleaning all the lies, the hypocrisies, the dead parts, whatever dross culture surrounds us and sometimes imprisons us with. Cutting through the forbidden means a lot to her in terms of freedom. The cloth is also a stage curtain, of course.

It was not a surprise to me to find out that when she was much younger, she wanted to be an actress. So did I. I went to America with the intention of studying theater, and ended up being a philosophy major. There are drives in the world of Maro Michalakakos that parallel mine, that is why I ended up believing somehow that we were destined to meet. She told me that she feels as if she is staging her art and directing herself, that she is actress/ performer and director at the same time, she likes being in control. With complete freedom, she delves into history, atmosphere, and architecture, even into the fantastic sometimes.

On one wall of her studio stood a work in progress, another of her birds, a vulture this time, but doubled, like in a mirror, like Narcissus. There are two vultures, in fact, connected, one drowning in another, spiritually.

Why this fascination with birds, I asked her. She reminisced about her childhood, playing with the chickens and the fowl in the garden with her brother. She confessed she was something of a tomboy. It is obvious that she likes playing with her fears.

Why this fascination with birds, I asked her. She reminisced about her childhood, playing with the chickens and the fowl in the garden with her brother. She confessed she was something of a tomboy. It is obvious that she likes playing with her fears.

Birds are free, beautiful but also terrible, she told me. She sees them as signs of communication, almost like angels. The idea of a snake changing its skin, or a vulture eating everybody else and remaining alone, these are the images that intrigue her. The vulture is an interesting take on narcissism. Maro always likes to play with the darker side of life, but never forgets to include the light.

There were remnants of works from an earlier time around her studio. I was especially taken with the series of metronomes, with arms or legs, like humans that have undergone strange metamorphosis. Even in this prosthetics of desire, extremes were reconciled with aesthetic delight, almost with humor, like in her birds coupling with mammals. I thought, here is an artist who taps resources of unprecedented expressiveness and here is a woman of exceptional warmth, a special new friend. That day in Athens was unforgettable.

There were and there shall be others, thankfully. We met again in September, had lunch in scorching heat, chatted about life and art. She had just shown some work at the Fethiye Mosque in Navpaktos, (ancient Lepanto) where the Ottoman Turks suffered their first big naval defeat in the 16th century. The Navpaktos project is a series of art shows engaging with cross-cultural currents and history.

Her installation was a banner of silk fabric, representing the finishing line of a race, with gold letters embroidered on it: “The Crushing Superiority of the Enemy,” written in French. I could think of a no more delightful way of satirizing war, or criticizing conflict. Making light of dangerous themes is the signature of Maro Michalakakos. She readily confesses that as an artist she wants to seduce her viewers, more than anything.

And then she announced to me that she was planning a big show about life, under the auspices of death. I laughed. Normally I would have been a bit concerned, but by now I knew of her take on death.

Back in April, in her studio, she had told me about a banquet she had staged for a charity benefit dinner. With her usual exquisite black humour, she had fashioned it as a funeral feast, where the guests would eat her, Maro, the artist, in effigy. She had cast her own form in sugar and koliva, a traditional sweet, and after this great dessert of cannibalism was consumed, there was music, dancing, and much gaiety.

With aplomb, she takes on things about which I would be superstitious. How come you can look at death with such directness, I asked her then. You live better, it is liberating, she replied, with sparks in her dark eyes. Typical Maro, I thought, smiling. She is right, of course. Awareness of mortality, and the ability to overcome our fear of it, enables us to be not only aesthetically but also ethically, and existentially free.

This aspect of her work is what attracted me to her immediately. Hers is a visceral, disturbing, but also spiritually cleansing art that never oversteps the boundaries of good taste, is always elegant and tender, yet extremely ruthless and lucid in its emotional truth. This is also why my encounter with her art echoed my discovery of Antonin Artaud when I was young. When I studied theater at Wellesley, many years ago, his book The Theater and Its Double was like a bible to me, and I thought that he was the prophet of the real revolution.

Artaud’s refusal of conventional, textual theater, his expectation that drama can give us access to our real selves and cleanse the toxins of social repression, his promise of a ritualistic, visceral, fresh theater had excited me in my youth in the same way that the drama in the installations of Maro Michalakakos invigorate me now.

Artaud’s refusal of conventional, textual theater, his expectation that drama can give us access to our real selves and cleanse the toxins of social repression, his promise of a ritualistic, visceral, fresh theater had excited me in my youth in the same way that the drama in the installations of Maro Michalakakos invigorate me now.

Of course, Artaud’s promise wasn’t fulfilled, the theater of cruelty never came about. It did affect and revolutionize the modern stage to a certain extent, with directors like Brook, Grotowski, and other more recent examples, but the spectacle aspect inevitably took over.

I feel that contemporary art in our day is now fulfilling the promise of Artaud more than theater itself, with performance art and an increasingly bold visual language.

The tender cruelty in the works of Maro Michalakakos is a case in point.

She stages our most fundamental fears and desires in their full extremity, but always with compassion and humour. Connection is important to her, simplicity brings her work richness, chaos makes her calm. She told me that the greatest danger in life is when you feel time is passing, but you don’t use your time fully. Maybe that is why she works with immigrant children in Greece, teaching them to make masks. When I visited Athens during Documenta in 2017, she had proposed a similar workshop for immigrant children to Rick Lowe, and participated in his Victoria Square project.

“What tortures me is the desire to be everywhere at the same time,” she told me.

“I need to be aware of and focus on how I want to be every moment, where and with whom.” Don’t we all, I thought. To overcome the dissipation of energy through fear is thus her most cherished longing. This gave me pause. I hadn’t encountered much wisdom in recent art, not her kind of instinctive wisdom anyway.

We did talk about what is happening in Turkey and in Greece now, of course we did. How the political climate in Turkey is becoming heavier, how the long-drawn crisis in Greece is forcing people to grapple with new fears.

It is the same with the fear of death. Maro dwells on it so much, because she feels death is the ultimate equalizer, it makes us all equal in life. But also, she is sensitive to other kinds of fear, the ones that rear up in the present oppressive, anxious atmosphere our two respective countries must deal with. Not to mention anxieties in the rest of Europe, or the impasse America seems to be in.

“It is fear that breeds populism,” Maro Michalakakos told me. “Imagine a country with the knowledge of and acceptance of fear,” she said. “Imagine a country without fear.”

Well, I am still imagining it, thanks to her.